For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood.1

Beloved, we are God's children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.2

Taking both of the above verses together, Sts. Paul and John indicate that our spiritual vision and comprehension are benighted and, moreover, that there is an integral connection between the depth of our capacity to see and understand, on the one hand, and the quality of our spiritual state of being in terms of likeness to God, on the other. Further, and more generally, for two or more beings or persons to communicate or cooperate as equals in fullness of mutual understanding, there must both be a reciprocal congruence in their capacities to perceive both each other and the world and to act in relation to one another in and through the world, else the meaning implicit in their words or activity might be mistaken for noise, and the communication between them distorted at best and severed at worst. God, of course, has no deficiencies in this regard, nor, truly, any deficiencies whatever. He sees, knows, and understands all things. Thus, because we are lacking in all these areas, God condescends in order to communicate with us, while at the same time helping expand our spiritual capacities in proportion to our effort along these lines, waiting patiently to communicate to us His mysteries with greater depth as we grow spiritually.

To explore some of these concepts more concretely, consider our perception of the activity of other human persons. When we see a man painting, we see him sitting, brush in hand, perhaps parsing his lips, perhaps furrowing his brow, making peculiar movements with his arm, hand, and fingers, carefully working to adorn the surface of the blank canvas before him with some combination of meaningful images—or, perhaps in the case of any number of recent forms of “modern” or “postmodern” art, intentionally ambiguous or meaningless images; in any case, some kind of interaction between the artist and the observer is intended—that is, some kind of meaning is being communicated, even if that meaning involves some highfalutin critique of art or society in general. I digress. At any rate, we see all this physical activity of the painter; but we, his fellow humans, see it as the activity of a creative being who has a purpose in mind and an idea or perspective on something to express, sometimes in symbol, sometimes “more literally”, for lack of a better term, to express simply the raw natural beauty he apprehends in creation (and to be sure, these purposes are not mutually exclusive, for “literal” creation is itself symbolic, as I have and will discuss elsewhere). In contrast, if the painter’s pet dog were to observe this same activity, it would doubtless not perceive the same depth of meaning as we do in the activity, nor in the meaningful product thereof—the painting as human artistic expression. The dog might perceive that its owner is generally preoccupied with something other than itself and thus move to reclaim his attention, but would certainly not perceive the activity itself as artistic. This is so, in general terms, because humans and dogs do not share the same nature—indeed, man has been bestowed, in relation to dogs, with higher spiritual faculties, and thus dogs do not have the eyes to see the human person in the creative activity of painting. As mentioned, the dog indeed sees something, but what it sees is limited, as a relatively lower form of life, by its nature and constitution. Even within humanity, different persons fall within a wide range of development across many dimensions, and so a given person (such as a small child) might not even perceive the painter’s activity as painting; nonetheless, human persons have the potential for such perception. For a being truly to work consciously and cooperatively with another at a given level, they must have something of their nature in common. If one being exists at a higher level in relation to the other, so to speak, the higher must condescend to the lower to achieve genuine collaboration. A dog is, by nature, incapable of truly collaborating with a human in the activity of painting. Perhaps a human could, in a guiding fashion, utilize the dog somehow in the process of his painting, but the dog would not be a conscious collaborator, nor aware of meaning of its role, and would, in this context, function merely as something akin to a human instrument; even so, such collaboration through condescension still has some form of heightening effect on the dog, and we can see this through the millennia of the domestication of their species. In contrast, a dog could more straightforwardly collaborate with a human in an activity like hunting; this is so because it is within the scope of a dog’s natural faculties to track, kill, and eat prey. It is true that a human, in hunting, could plan and execute tactics and strategies higher than a dog’s ability to comprehend, and could utilize the dog in them without its explicit awareness, but a dog is nonetheless—even if through man’s condescension and conscious guidance—capable of collaborating genuinely with humans in the activity of hunting precisely because the dog itself has the capacity to hunt. I present these simple examples, although not precisely analogous, as a starting point from which to consider human collaboration with God. Thus, having considered these dynamics at a lower level, let us consider them generally in the context of man’s relation to God.

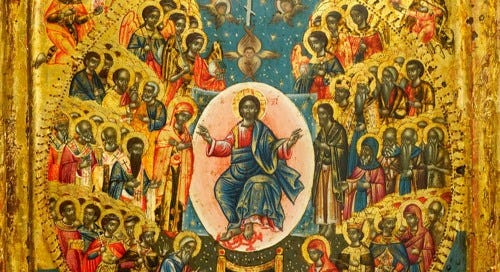

Since Christ has assumed our human nature into His person as one who is also by nature divine, as the Creator and man’s Archetype He has bestowed him with the capacity for higher spiritual vision and activity, which he develops—his divinization— through co-laboring with God; accordingly, the Spirit draws him upward into a state in which he can begin to perceive all of creation as the activity of God—to see God, despite His infinite transcendence, concretely and experientially in his energies: as divine Person acting in and through all things with infinite wisdom, goodness, and love. God so calls and lifts up the being of man to establish and bring him progressively into the fullness of communion, and thus into collaborative dialogue, with Himself. The concomitant spiritual vision God grants is necessary for man genuinely to communicate and act in tandem with the Divine. The difference between such purified spiritual perception and that of fallen man, who is imprisoned by his passions, is akin to the difference between how we might imagine a horse fly to perceive a wedding ceremony (in whatever its infinitesimally limited capacity, even if only as some extremely crude external stimuli which, to the fly, have nothing to do with a wedding ceremony), and how the bride and groom in that very same ceremony perceive it. These two perceptions constitute two entirely different worlds, with that of humans doubtless being incalculably vaster. But because it comes in gradations along a continuum, the beauty of developing this spiritual sight—seeing God acting through the created order—is that whatever one’s current level of development, there he stands somewhere on the slope of an infinitely high mountain. As he ascends, though the hike be an endless one, he is to that extent able from its heights to perceive a new earth in the light of new heavens.

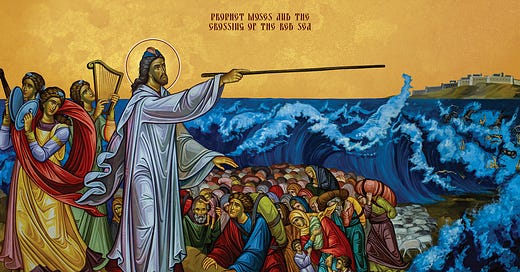

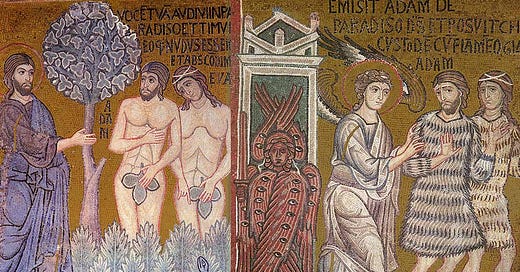

Since we have fallen and dwell within a world marred by sin, our spiritual vision is, at best, clouded, and, at worst, entirely inverted. In his initial innocence, man was in Paradise with God, though he was not yet spiritually stable in this state. God intended to test man in order to confirm him in virtue and, with his cooperation, continue to draw him along the path toward ever-deeper communion with Himself. But man opted for his own way; he fell. God thus sought man in his fallen condition in order, ultimately in Christ, to become the way out of the pit man dug for himself. To get a glimpse of where man is going in his spiritual development, it is helpful to consider where he was before he fell:

In the condition that was his from the beginning, man saw in all things, just as the saint does, gifts continually being offered by God and words continually being addressed to him through the various circumstances brought about by God. Nature itself was a diaphanous medium of the present activity and speech of God. Only when sin blunted the acuteness of man’s pure sensitivity to God, who works and speaks through created things, did the necessity arise for a revelation that differed from the activity that God was still carrying on at every moment through the medium of creation, but no longer perceived by man. Before that time God walked continuously through the transparent “garden” of the world.3

I would venture that most humans since Adam’s fall, barring the great saints of the Church, have not so walked with God in the transparent garden of the world. And while, from our perspective, assuming that most who are reading this—myself included—are not saints, this is a substantial and wondrous feat. At the same time, it is impressive precisely because those who have attained such spiritual heights have done so as fallen and from within a fallen world. After all, Paradise was Adam’s initial abode, when he was free of sin; as such, his dialogue with God through the created order flowed much more freely; now, when we fall through sin, it is by repentance—through which God heals us of our spiritual wounds and cleanses our sinful hearts which obfuscate our spiritual vision—that this dialogue can, for us also, flow more freely. Honest ascetic labor is the only path upward. Just as God pronounced to Adam that it would be by the sweat of his brow that he would obtain food to live, it is by the sweat of ours that we must sew spiritual seed and reap spiritual fruit. Though this labor is difficult, God will be with us in it. Often, on the long road of repentance, He gives us a foretaste of what awaits us in our spiritual development so that the flame of our hope is not extinguished prematurely. I have found much in the writings of St. Dumitru Stăniloae which has fed this flame for me—specifically in The Experience of God, Volumes 1 and 2, the latter being what I am reading currently—and in the remaining portion of this article, I offer some reflections along these lines, building from what has preceded.

Human persons are conscious, willing, active, and bodily subjects—living loci of free agency; we exist, simultaneously, both imminently within and transcendently above the world. All these aspects of the constitution of our being, and, indeed, the whole of our being itself—our very selves, and all that we have or ever will have—we have received as a gift from God. Having so received ourselves, and all of creation, which was called forth from nothing for our sake, as a gift, we are bestowed with the royal responsibility of cultivating ourselves, each other, and the whole of God’s cosmic garden into a state of perfectly harmonious spirituality and love. To this end, God made human persons rational, creative, and communally relational beings, oriented both toward other subjects as their dialogical equals, and objects as the symbolic currency of their creative communication. Sacrificial love is our lifeblood, and creative transformation is the mode of our mutual self-offering; our giving gifts to God and each other is constitutive of and inseparable from this self-offering. Accordingly, all gifts are personal, and anything we give—even something as seemingly insignificant as a cold glass of water to a stranger—is a gift of self through what is given. We give ourselves through the transformation we impart to nature, the product of which, in its new form, we share with others. We find a source of clean water, put it into a vessel for drinking, and offer it to another; in so doing, we take materials from nature, transform them into something new and suited to a purpose, and offer this new unity—the glass of water—as a gift; this act is an expression of love because it contains ourselves within it, and through it we give ourselves to another. As humans, our interaction with God and each other, through the medium of the created order, is fundamentally dialogical. God, in his act of creation, laid the necessary groundwork for a dialogue with man, and, in His creation of man himself, initiated this dialogue. Because of creation’s dialogical purpose, meaning is foundational to and inseparable from reality. Creatures at levels below man in the created order were made by God to bear meaning between human persons in the context of their communion with Him; and to the extent that they do so, they become real. Their becoming real is also, through man, their humanization—and to the degree that he has developed into the likeness of God, their divinization. All things, then, have their peculiar meaning and purpose in this dialogue between man and God in communion.

Our vocation as God’s sons and the royal priests of His household is that of creative cultivators of the world. The medium of our operation is the symbolic world in which we live, and we experience our development therein as the joyful ecstasy of uncovering and creatively expanding creation’s potentially infinite, living, and dynamic map of meaning. When we experience something truly new through creative effort, we offer the fruits of this effort to each other in order not only that each might share in the spiritual exhilaration of this expansion of the frontier of creation, but also that each subsequently might offer his unique contribution. Humans collaborating—laboring in communion—multiplies exponentially the gifts we receive from God, who gives to each person for the sake of all jointly, and all things jointly for the sake of each. The purpose and dynamics of this of labor which God has given man to do is encapsulated well by St. Dumitru Stăniloae in The Experience of God, Volume 2:

[T]he process of making the contingency of the world actual and thereby elevating the world into continually more spiritual states in company with humans who transcend themselves in the direction of communion with the infinite Person and in the direction of their own continual enrichment from that Personal source—this process is a work that belongs to the human spirit in the body. The world itself, apart from the human spirit, would not be able to break out of the rigid linear framework of automatic repetition. Through its own strengthening, which is identical with the complete liberation of the spirit from the slavery of those passions that automatize it, the incarnated human spirit can free nature, too, from its own automatic repetition. The incarnated human spirit is a mirror which, through the process of sensing and thinking that are mediated by the body, consciously gathers within itself the reasons and images of created things and makes of the entire world a unitary image of its own consciousness. On this basis, the spirit—when it moves according to its own genuine aspirations and reason—intervenes in a certain manner in created things and in the forces of nature, combining and directing them according to its own wishes toward a transcendence that is good.4

Meaning is grasped when purpose is mediated consciously; fullness of meaning is communicated when gifts are given and received freely between persons. Because our purposes and meanings are all interrelated and nested hierarchically within each other in many layers and branches, and because meaning is foundational to genuine reality, our interpersonal communication—whose quintessential aim is to facilitate the giving and receiving of transformed creation as gift, ultimately to God—in order to be effective, must take on the symbolic shape of creation. At the same time, the symbolic shape of creation is a function of our communication, as we are, in Christ, the macrocosmic center of the world and free collaborators with God in His ongoing act of creation. Indeed, there exists a symbiotic and dynamic relationship between our dialogue with each other and God, on the one hand, and the symbolic shape of creation, on the other. This is precisely because the natural order of creation, of which we are both a part and yet transcend, is the medium of our communication. Because we are the bearers of God’s image—and specifically because we are free and transcendent personal agents with respect to the world in which we exist bodily—our communication is also creatively transformative of the medium itself. But because this creative transformation is synergistic, involving both us and God as active participants, and not us alone, the meaning we discover in the cosmos has the paradoxical quality of being both revealed from above by God and the product of our creative efforts simultaneously; on the one hand, Christ, the Logos, contains the infinity of all meaning and purpose within Himself and is the One in whom they are ultimately revealed, but, on the other hand, we are active participants in their actualization in the created order which, in its initial and developing condition, is a vast sea of potentiality. This creative actualization occurs through human work, which necessarily involves our conscious exercising of the free, personal agency we have as images of God, as freedom is a necessary condition for creativity. Such freedom, of course, is not the bald freedom to “do what thou wilt”, as it is often conceived of and characterized by modernity, but rather the freedom from any impurity which bars one from resting actively in God’s boundless, trinitarian communion of love, and consequently the freedom to actualize the good, creatively and in collaboration with Him in Christ. This love is the foundation for God’s initial and ongoing creative act. Indeed, only God knows what is creatively possible for man when equipped with the freedom of eternity, which comes with his dwelling in this love; for, as it is written, “[N]o eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him” (1 Corinthians 2:9).

In light of all this, we ask: for what—and, perhaps more fundamentally, for whom—is the world? The world is the flexible and dynamic created medium through which the infinite God, as triune personality, is expressed to us progressively—and through which we express ourselves in response—in our spiritual trajectory toward fullness of communion with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Vis-à-vis their telos, all things are for the God-man Christ, the only-begotten Son of the Father, and likewise for us in Him as adopted sons and fellow heirs of the divine inheritance, given by the Father as gifts so that we, by the Spirit, in the Son—who Himself is in the bosom of the Father before all ages—may participate in a creative, eternal, and ever new dialogue of love together with the persons of the Holy Trinity.

1 Corinthians 13:12

1 John 3:2

Stăniloae, The Experience of God, Volume 2, p. 105.

Stăniloae, The Experience of God, Volume 2, pp. 56-57.

Yet another beautiful reflection. I suggest that it’s more accurate to view Nature not as symbolic but as truly sacramental - the very revelation of God’s manifest presence as creation. Likewise, St. Dumitru called Nature itself “the diaphanous medium of the present activity and speech of God.”

It’s also worth carefully noting that sin “blunted the acuteness of man’s pure sensitivity to God” - that is, Nature didn’t change, but rather man no longer saw sacramental Nature clearly.

So what was the solution? Again, let’s pay close attention to what St. Dumitru says: “the necessity [arose] for a revelation that differed from the activity that God was still carrying on at every moment through the medium of creation, but no longer perceived by man.” Obviously, he’s pointing to the Incarnation.

However, notice that St.Dumitru does not mention an inherent or resultant ontological separation or rupture between God and man due to sin. Man simply no longer perceived the sacramentality of Nature and forgot who he is and his great high calling, which God gave man as the very purpose and meaning of his life.

The Incarnation then was not about uniting or reuniting ontologically separated God and man (or creation), but rather fully revealing to man that which he no longer saw clearly, inspiring man once again to take up his divine calling. As vitally important as it was, salvation was not a necessary result of the Incarnation. Salvation is theosis - the actualization of the inherent, essential, divine potential of man (and Nature), consciously manifesting God’s life as the world, as sacrament. To see this clearly and live it is a Eucharistic life of conscious communion in and as and with God.

PART II: (read "PART I" first)

7) "The world itself, apart from the human spirit, would not be able to break out of the rigid linear framework of automatic repetition." This is also a fundamental idea in my B-Model, where the world is gathered in a reflecting microcosm and, through spontaneous signals or power, is directed in a certain direction by input-output feedback. The question, however, is how this fits with the A-Model, which I will briefly touch upon in a moment.

8) Why negate freedom "to do what thou wilt" and affirm freedom from impurity when one could affirm both, and that what thou wilt, if purified, is necessarily good?

9) "God, in his act of creation, laid the necessary groundwork for a dialogue with man, and, in His creation of man himself, initiated this dialogue. Because of creation’s dialogical purpose, meaning is foundational to and inseparable from reality."

Beautifully said.

The way I understand this truth in metaphysical analysis is, roughly, as follows. The A-Model is based on the Theodical Argument and the Word-Machine, in specific on the idea that God’s input for creation was unspecific, and another world could have been created by Him, or even no world at all.

We can distinguish between interaction that occurs between entities via energetic or informative exchange (= IE), which I already established I think is between hypostases, and interaction that occurs between entities due to Mutual Interiority (= MI) which is that what a being has.

Once I asked how *IE* (energetic or informative exchange) is reasonable to assume if we already have MI (Mutual Interority), and the answer given to me (by multiple people) was that it is reflected from the Trinity, where it is true between the divine persons. However, what makes us say that IE is proper to beings and not hypostases & persons? If it is proper to hypostases, then we cannot say that the Trinity tells us it is possible between created beings, as the hypostases of God interact via IE but are all [of] one substance or being. Now, there is IE between God and creation by sustainment and energetic participation. But if one can say that between created beings (or entities in general) there is MI and not IE because communication, in the end, serves harmony (or a development into harmony,) which one can get to by MI with the act of creation beforehand, wouldn't that be coherent and have all explanatory power?

In short, let us imagine infinite many universes, and each universe is richer than the materialistic one for it does not only contain all its content, but also the phenomenal aspect of a point of perspective around which the universe is stretched. Each point in that world corresponds to one universe which is that world reflected from that point (in different gradiants of specifity, and for most perspectives unconscious; without senses, thoughts or emotions.) Thus, each world contains infinite many universes.

It is completely by the own notion and spontaneity, what that universe reflects. Perhaps it is ordered, perhaps it is not. The point is, God only creates a world (a set of universes) if they are coherent with each other, and if they belong to the set of best possible worlds.

To be coherent with each other, they need to be mutual indwelling, because they are coherent only when they reflect each other within themselves.

Thus, God creates a world of infinite many, mutual indwelling universes (which is each point of that world reflected from that point.) Now, the own developement of each mutual indwelling universe (which is a substance or "being" in the non-personal sense) would reflect the whole harmony and interaction without need for IE except with the sustaining power of God and the many energetic manifestations of the divine energy intersecting each universe.

10) The purpose of communication is harmony, defined as the optimal arrangement of parts within a whole: realizing and manifesting the inherent logical connections between all parts, and serves to convey truth, build relationships, share knowledge, and resolve conflicts by alignment of individual perspectives.

If God created the world in a way where each part (point-universe) is self-developing into their harmonious role, then communication is necessary insofar each notion is logically contained in all others since their inception (which is mutual interiority [MI]/communal ontology) which makes any other sort of communication (= IE) not only unconceivable (in a way logically functioning) but also arbitrary. The exception of course are the divine energies who make the development of the universes and the perceptive manifestations (cosmos → microcosm) possible.

11) How, then, can compatibility with point 7) be achieved?

Each universe proper to a [human] soul is dominant in determining what world emerges, thus, which set of infinite many point-universes come about or can even come about concerning God's coherence. This means that it is humans who determine the coherent picture, and everything else follows as an effect to make the picture coherent, but is not directly chosen, only indirectly as a bridge between what is chosen: universes proper to humans.